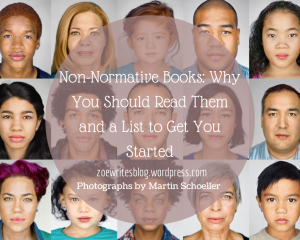

In an increasingly globalized world, it is baffling that the US’s mainstream books are so overwhelmingly homogenous–by which I mean white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant or Catholic. International travel and communication is getting easier all the time, and we can see how countries are becoming ever more closely linked. For an example, just look to the European Union. Not only is the world becoming smaller, but the United States itself is becoming increasingly diverse, with the Census Bureau projecting that the white majority will be overturned by 2043, and sooner for younger age groups. The population of minority children under the age of five was 49.9% in 2012 (NBC News).

Click on this link to read an article by Lise Funderburg for National Geographic, with photos by Martin Schoeller, to have a powerful visual experience about what exactly these stats mean.

What do these statistics mean? They mean that the publishing industry is behind the curve. They mean that it’s past time for some change.

Currently, the industry’s labeling system is such that books that feature non-normative characters are labeled as such. Books featuring black characters and communities are relegated to African American & Black or Multicultural sections. So are books dealing with gay/lesbian themes. You name it. Everything is set up so that the non-normative features are highlighted. The implications can be dangerous and we are left feeling that anything non-normative is “the other” and therefore not worthy of our time and energy because the author or the characters are outside the mainstream. What could they possibly have to say to the “rest of us?”

I would argue that this is a dangerous and limiting practice and attitude. There is an underlying assumption that those books that are left–overwhelmingly “Literature” featuring male WASP characters with male WASP authors featuring themes especially relevant to male WASP people–are what is “normal.” Within WASP culture, even women authors are too often shunted off into “women’s fiction” so that only the men are left. (Read this article for an all-too-common example of this practice.) This trend mimics that of the male, WASP-dominated publishing industry, long seen as the arbiters of what makes “art” or “good literature.” All of this is to say that our books, a vital part of any culture, is excluding and even looking down upon a large and growing chunk of ours.

It is important to read and support these non-normative books. Towards that goal, I have compiled a list of 10 books that are worth reading for their own merits, but especially so considering their content and/or authors. I am embarrassed by how hard it was for me to come up with this list and how many people are not represented. As such, I whole-heartedly welcome any suggestions for further reading.

- Lilith’s Brood by Octavia E. Butler

- 100 Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

- When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka

- The Bonesetter’s Daughter by Amy Tan

- First Test by Tamora Pierce*

- The Sowing by K Makansi

- Island of the Blue Dolphins by Scott O’Dell

- King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild

- The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros

- Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi

There are a couple of great resources that are continually tackling this very issue if you are interested in joining the conversation:

* While Tamora Pierce has certainly created a world with lots of cultural and ethnic diversity, the one thing that made me choose this book (and series) in particular out of all her others is that this is one of the only books I have ever read that has a main female character who is seen as fat, stocky, mannish, and even ugly in a world that prizes women who are the opposite. As someone who has always struggled with weight, body image, and self esteem, I can’t tell you how refreshing and inspiring it was to have this kick-ass character to look up to and with which to connect.